Source: Il Sole 24 Ore - Domenica 2023-10-08

Translation from Italian: lamescholar - 2023-10-30

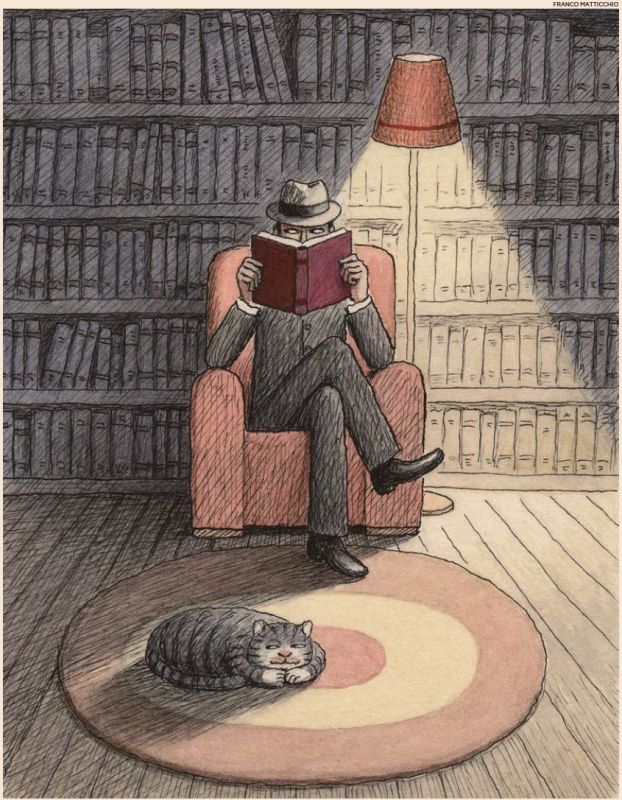

PRAISE OF READING (AND THE NEW HUMANISM)

The ways of knowledge. From Cicero’s “humanitas” to today: it is necessary to educate, as James Baldwin teaches, the imagination and not to replace the old chains with the new, the old prejudices with the new

by Alberto Manguel

My library has changed throughout my life as I myself changed. Its contents have changed, this is obvious, for a month with the other and for a year with the other, and also its physical location has changed while I was leading my traveling life. But most importantly, its identity has changed as it changed my own identity as a reader: my library, like every library, is a symbol of belonging to the human race, the humanist symbol par excellence.

Describing André Gide in his book Two Cheers for Democracy, E.M. Forster stated that Gide was not a hero, but a humanist. “A humanist,” continued Forster, “has four main characteristics: curiosity, a free mind, faith in good taste and the human race.” As a definition of the common use of the term “humanist,” it could also go, but unfortunately or fortunately this term has suffered innumerable tidal changes, since a first trace of its meaning already appeared in the Cicero writings. The humanitas of Cicero, rooted in Greek thought, required a combination of faculties to define the human animal: prescient, wise, complex, acute, full of memory, reason and prudence. Associated mainly with a rationalist perspective, humanism became the pillar of various theories of education, both in the Italian Renaissance, thanks to luminaries such as Angelo Poliziano and Marsilio Ficino, and in Northern Europe, especially with Erasmus. Later, thanks to the political theory of the Enlightenment and materialism in the nineteenth century, the term humanism will come to embrace every area of human activity, from religious ethics and from the existentialism to the pacifist movement.

Like other terms - democracy, equality, race, gender - humanism has come to mean almost anything about human works, good or bad, depending on the opinions of each. In this sense, talking about a new humanism is at best redundant, and at worst false.

But somewhere, in the meanderings of this expression, the vague sense of an optimismistic faith in the Cyceronian triad is still undoubtedly present: memory, reason and prudence are precious qualities even today, at least as redemptive aspirations. Our libraries conceal pages that tell of miraculous feats and daring ideas, which could be like that handful of souls by virtue of which eternal salvation has been promised to our species, and these actions and words, if we take them as evidence of humanism, could justify the resurrection of what is best in the human race. And then we also invoke a new humanism, if this means becoming the heirs and rivals of Galileo and Dante, of Averroe and Maimonides, of Ugo of St. Victor and Ibn Tufail.

Unfortunately, the view of the world from this third decade of the 21st century is not much encouraging: the persistence of capitalist greed, the disregard for the minimum requirements to prevent catastrophic climate change, the inability - or refusal - to manage involuntary mass transfers, the recurrence of slavery under new names, racism, sexism and homophobia deeply rooted in most of our social systems, the triumphant return of fascist populism, the disconcerting Cassandra has thrown in the towel and is ready for retirement, while Giovanni Battista has launched his latest shouts in the desert.

Cicero invented the term humanitas to explain his idea of what would become known, centuries later, as humanistic education, an education that would nourish curious minds with the intelligences of the past and allow present generations to equal and even overcome their masters. Cicero had in mind the formation of capable citizens for his ideal republic. Two millennia later, even taking into account today’s values and challenges, the aim of education should still be the same: not to train our young people to become slaves to the system, but to teach them to increase their imagination to face it. In 1963, James Baldwin, in a speech to American teachers, after stating that we are living very dangerous times, summed up the problem of an authentically humanist education: “The paradox of education is precisely this: that the more you become aware, the more you begin to doubt the society from which you are being educated.”

As Baldwin knew, this is an inevitable paradox.

However, there is a harmful form of new humanism that is today, consciously or not, subverting the Baldwinian idea of what education should be: demanding quotas in place of evidence of merit, imposing racist restrictions while declaring that it wants to eliminate racism, exalting works of low quality in the name of non-exclusion, punishing the true humanists who have long raised their voice against prejudice and injustice, subjecting them to a judgment without trial Baldwin spoke of educating imagination, not replacing old chains with new chains, the ancient prejudices with self-censorship. Baldwin’s paradox, healthy and subversive, is the inspiration that originated the Centre for the Study of the History of Reading in Lisbon: built around the library of 40 thousand volumes that I have accumulated over the course of seventy years, a multilingual collection of literary and humanistic works that I have donated to the city of Lisbon.

THE BOOK

The article on the page is taken from the book by Alberto Manguel, A History of Reading. New edition expanded and updated (Vita e Pensiero, pp. 376, € 25). The book is now re-proposed in a new edition expanded and updated. Manguel proposes a story of reading that each reader can feel as his own. There is no chronological layout, but thematic chapters rich in anecdotes, personal notes, tasty stories and unforgettable characters.